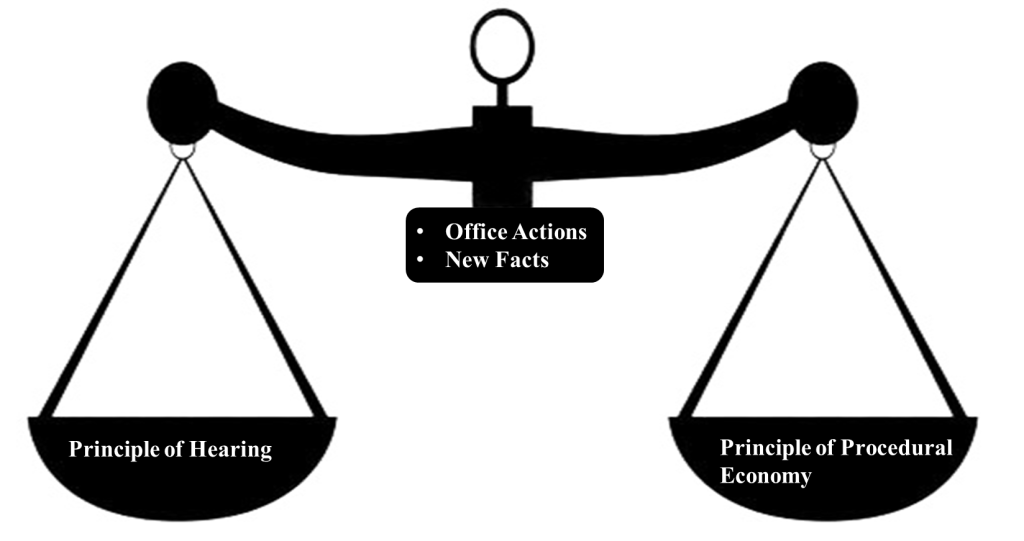

The Principle of Hearing and the Principle of Procedural Economy

In the examination procedure of CN patents, an examiner should consider the balance between the principle of hearing and the principle of procedural economy.

Principle of Hearing

According to the provisions of Chapter 1. 2.5, Part IV of Guidelines for Patent Examination of China (shortened as Guidelines):

Before an examination decision is made, the party adversely affected by the examination decision shall be given an opportunity to make observations on the grounds, evidence and the ascertained facts on which the examination decision is based, that is to say, the party adversely affected by the examination decision shall have been informed by means of communication, document exchange, or oral proceeding, of the grounds, evidence, and the ascertained facts on which the examination decision is based, and given the opportunity to make observations.

Where, before an examination decision is made, the patent applicant or patentee has been changed according to an effective judgment or an effective mediation decision made by the People’s Court or a local intellectual property administrative authority, the party concerned after the change shall be given the opportunity to make observations.

In the substantive examination, when the examiner makes a decision of rejection, the facts, grounds and evidence for rejection shall have been notified to the applicant, and the decision shall not contain any new facts, grounds and/or evidence.

According to the provisions of Chapter 8. 6.1, Part II of Guidelines:

Before making the decision of rejection, the examiner shall notify the applicant the facts, grounds and evidence confirmed by substantive examination upon which the conclusion is based that the application is considered to fall into one of the circumstances where an application shall be rejected as specified in Rule 53, and provide at least one opportunity for the application to make the observation and/or amendments.

The decision of rejection shall usually be made after the second Office Action. However, if the applicant, within the time limit specified in the first Office Action, has not put forward any convincing observations and/or evidences for rejectable defects as indicated in the Office Action, or has not amended the application documents in answer to such defects, or the amendments have only corrected the wrongly written characters or altered the presentations without modifying the technical solution substantially, the examiner may make a decision of rejection directly.

Generally speaking, the decision of rejection is made after two observations and/or amendments. However, if during the first observation, the applicant has not put forward convincing response or acceptable amendments, the examiner may make the decision of rejection. On the contrary, if the applicant has put forwards convincing observations or make proper claim amendments, the examiner will issue a second Office Action based on the principle of hearing even if the defects which can be rejected by the grounds and evidence previously notified to the applicant still exist in the amended application documents.

Principle of Procedural Economy

According to the provisions of Chapter 8.2.2.3, Part II of Guidelines:

In the course of substantive examination of an invention application, the examiner shall make the examination procedure as brief as possible. In other words, the examiner shall try his best to close the case as early as possible. To reach this aim, the examiner shall indicate all the defects of the application which are not in conformity with the Patent Law and its Implementing Regulations in the first Office Action and invite the applicant to make response for all the issues within the specified time limit, unless he is sure that the application is not possible to be granted the patent right. The correspondence between the examiner and the applicant shall be reduced to the least to economize on procedure.

However, the examiner shall not neglect the principle of hearing for the reason of economizing on procedure.

That is to say, the principle of hearing comes before the principle of procedural economy. If the facts upon which the rejection is based have changed when the applicant has put forward convincing response or acceptable amendments, will this make the application maintain examination status as long as possible? The answer is no. That is because the examiner needs to balance the relationship between the principle of hearing and the principle of procedural economy.

Balance Between the Principle of Hearing and the Principle of Procedural Economy

The No.[2002]52 document issued by the CNIPA in 2003 provides some instructive opinions regarding the balance between the principle of hearing and the principle of procedural economy. The document states:

In principle, as long as there exists new facts not mentioned in the previous Office Action, the examiner shall issue new Office Action. However, in the substantive examination, for amendments that are out of scope, the examiner shall make the decision of rejection after at least two Office Actions are issued in order to balance the principle of hearing and the principle of procedural economy.

During the examination procedure, an examiner should consider the balance between the principle of hearing and the principle of procedural economy. The fewer the office actions, the more important the principle of hearing, while the more the office actions, the more important the principle of procedural economy.

For the principle of hearing, it is usually used during the first and second Office Actions, while for the third Office Action, the applicant should use the principle of hearing with cautiousness. And for the fourth and subsequent Office Actions, its use has ridiculous restrictions. For the principle of procedural economy, it will be attached more importance after the second Office Action. Therefore, the applicant should pay more attention to the claim amendment for new facts when or after the second Office Action is issued. Otherwise, the examiner may consider less or even ignore the principle of hearing and directly issue the decision of rejection. For example, if the applicant simply puts forward arguments while not amends the claims when responding the second Office Action, the examiner may issue Notice of Rejection based on the principle of procedural economy.

If in the second or subsequent OA response, the claim amendments are beyond the protection scope of the specification, the examiner may issue a rejection. Therefore, if there is any chance of the response out of the scope, the applicant may decide whether to take the risk depending on the examination stage. Careful consideration is necessary to avoid receiving final rejection.

It can be seen that the examiner will balance the two principles during examination. Accordingly, the applicant may have one or more chances to make observations. As to how many chances the applicant may receive, it depends on the specific situation of the responses. When responding, the applicant may use flexible response strategy based on the possible conditions to create more response opportunities.

With respect to OA responses, China and the US have certain differences. From the perspective of practice, China has restrictions on examination, which means the applicant cannot submit argument constantly based on new facts. In addition, whether the claims have been commented or amended is an important factor for the examiner to decide whether to close the case. Moreover, during the first examination, a Chinese examiner may give adverse opinions on dependent claims based on limited documents. Therefore, when drafting Chinese invention patent applications, the applicant or the agent should plan targeted claims rather than simply copy the claims of its US counterpart.

Additional information

As mentioned before, the applicant could put forward new facts when amending claims. However, it does not mean that new facts can be generated as long as the claims have been amended. A new fact refers to a technical solution corresponding to the amended claim that has not been commented by the examiner during the previous examinations. There are two possible conditions wherein new facts may be created:

- The feature brought in the independent claim comes from the specification, and this feature is not included in all claims;

- The feature brought in the independent claim comes from two dependent claims that have no reference relationship.

Here is an example of the second condition:

The claims that have been commented by the examiner: claim 2 depends upon claim 1; claim 3 depends on claim 1; claim 4 depends on claim 3…;

Methods of amendment: 1) Claim 1+2; 2) Claim 1+3; 3) Claim 1+2+3;

Among the above methods, 1) and 2) only contain technical solutions commented by the examiner, but have not brought in new facts. Namely, these two methods do not satisfy the principle of hearing. As for 3), it satisfies the principle of hearing because combination of claim 2 and claim 3 compose a technical solution that has not been commented by the examiner.